History the Building of the Mahanoy Tunnel

By Jane M. Lyon - 1905

Michael Barry and a man named Bauns entered into a contract with The Little Schuylkill Co. to dig a tunnel between Mahanoy City and what is now known as Lakeside.

Bauns retired before the work was begun, and sold his place and interest in the contract to Phillip and Patrick J. Barry, brothers of Michael Barry. P.J. was made superintendent and lived near and took charge of the works. The head engineer was a man named Anderson, from Tamaqua. The tunnel was begun in 1859 and finished in 1862. The time and date are marked on stones at either end of the tunnel.

During the three years of constant work in drilling and blasting not a single accident occurred, nor was there a single man hurt. There was rare fight between different factions, at that time known as the “Corkonians” and the “Fardowners”- an old world feud which has long since died out in the New World’s freedom of thought and speech.

But most of the workmen were new and held a grudge against each other to such an extent that they would not exchange shifts, or hold communication in any peaceful way. The day shift was from 6 o’clock A.M. to 6 P.M., with an hour for dinner. The night shift was from 6 P.M. to 6 A.M., with an hour’s rest at midnight. Eleven hours’ work for each gang. The heading men, who worked at the top, where was the more danger from falling rocks, were paid seven dollars a week. The bottom men eighty-seven cants a day. “A Round” was putting a hole into a rock for the purpose of blasting. It took two men at each drill, one holding and one striking. They had five pairs of such men in each heading. They were each to drill seven rounds, or seven holes for a day’s work. When the fight began between the two set of workers, the day men made eight holes for one shift; then the night men made nine. They kept on increasing the number of rounds until they reached fourteen. Then, getting tired of such strenuous labor, they all dropped back to seven rounds. The Barrys refused to accept seven rounds as a day’s work. They thought that men who could do fourteen holes for spite could drill the same for pay. They finally compromised on eleven rounds for a day’s work, and were paid on that basis until the tunnel was completed.

THE RIOT

Pat. McCann was the leader of the “Fardowns.” He kept a “speakeasy” below Heidenrich’s farm. O’Donnell was the leader of the “Corkonians.” He was a tamper breaker of rocks. Frederick Reidinger, now living in Mahanoy City, 1905, was the head blacksmith for the Barrys during the whole time of the excavation of the tunnel, and lived right on the spot. This report of the troubles between the factions is taken from Mr. Reidienger’s own experience and knowledge. He had made an immense hammer for this O’Donnell to break the stone which was used to tamp down the powder in the drilled holes. One day O’Donnell was in the blacksmith shop when McCann came in. They at once began spatting with each other, when O’Donnell, became furious t something that McCann had said, picked up this tamper and struck McCann, and nearly killed him. It was thought he would die, but in a few days he was around again blatant as ever. The superintendent when he heard of the fight discharged the two men. O’Donnell went away, but McCann hung around. When he was able to work, Hugh Dolan, the headman on the Fardowns’ shift, put McCann on a job without the knowledge of the Barrys. P. J. Barry, at that time in charge of the works, lived right at the tunnel in the mess tent. He went into the tunnel and, finding McCann there working, ordered him out. He went, but the rest of the Fardowns dropped their tools and went out with their leader. The Barrys then for a while worked only one set of men. But the Fardowns were continually annoying those who kept on working, waylaying them, badgering and stoning them.

Some of the idle men were married and had their families living in little shacks near the tunnel, and winter was coming on, and the money was getting scarce. They finally went to the Supt. Barry and asked to be taken back. He agreed to, and did take back the married men; but refused to take the single ones, as they were agitators. A few days before New Year’s, 1860, there were notices put up in the tunnel and outside the blacksmith shop, stating that if P. J. Barry, Supt., did not take back every one of these idle men, he would have to face “THIS,” and “THIS’ was a well drawn revolver. Mr. Reindinger sent word to the Superintendent about these notices, and Barry told Hugh Dolan to tear them down and to tell these men plainly and distinctly that he would not take back one more of these men, not a single man.

On the Saturday night before the New Year a number of men surrounded Barry’s shanty and called him to come out and talk to them. He called through the door that he would talk to them, but that he would not come out. They said they would ask him six times to come out, and if he did not come after the sixth call he would have to take consequences. He did not come, however, after the sixth call, nor before. His bedroom in which his wife and three children were sleeping was back of the eating room in the shack. He placed his family flat on the floor under beds. His nephew, Mike Barry, and brother-in-law, Paul Decker, were sleeping up in the loft. When they heard the racket they came down. They gathered all the firearms in the shanty together, and the three men threw themselves on the floor in the bedroom. The Superintendent, sliding up the board window a couple of inches, lay under it and fired through the opening. The first shot was fired by the outsiders. There was an answering shot from inside, which caused a yell of surprise. The rioters sent thirty-six bullets through Barry’s bedroom, and he sent quite as many, if not more, hurling through the crowd. The boys would keep the weapons loaded and push them along the floor to Barry, who would raise his arm to the opening and fire. None of Barry’s people was hurt. One man was killed outright and several wounded among the attacking party. There must have been more than fifty in the mob of rioters, as twenty-seven of the reached Hometown quite exhausted, at six o’clock the next morning. A number of others went to Summit Hill, which was then called Old Mine, and never heard of afterwards. Barry, the Superintendent, went to Tamaqua, got a constable and a posse, followed the trail, and arrested the twenty-seven men located in Hometown. Every man arrested was a Fardowner, and every man at his trial proved an alibi. Seven men who boarded at the same shack as Fred. Reidinger were also arrested, and he had to swear that these men were in the shanty the night of the raid.

The Trouble with the Company

In the contract The Little Schuylkill Co. agreed to pay the contractors, and afterward did pay, one hundred and twenty dollars a running yard for the digging of the tunnel. A part of the money due the Barrys was retained by the company to provide against accident, or loss, or failure to comply with the agreement. So when the tunnel was finished the company owed the Barrys sixty thousand dollars, and the Barrys owed three months’ wages. The following statement, which may as well be interpolated here, is taken from a written communication made to John T. Quinn, of Mahanoy City, by John G. Gorman of Wentworth, Lawrence County, Missouri.

“After the tunnel was completed the Little Schuylkill Company ran a locomotive through it to see if it was in working order. Mr. Gorman was on the engine when it went through the first time, and when it reached the west end the engine struck a rock and was ditched. They backed it up, got it on the track, and ran through and on to Mahanoy City, where P. J. Barry gave orders to all the hotels and saloons there at that time that all workmen, civil engineers, railroad hands and officials were to be given all the eatables and drinkables each wished, at the expense of the Superintendent. After a few weeks the Barrys’ received a dispatch from their counsel, then in Harrisburg, that the road had changed ownership, that the Philadelphia and Reading Co. had bought out the right, title and interest of The Little Schuylkill Company, and that the Barrys should not allow the engine to pass over the road until they had received the money due.

Mr. Reidinger says that he never knew of a Gorman that was any way connected or interested in the mining of the tunnel, or of and such man being on the first engine, or of the first engine being derailed, yet it might have happened. There was a Gorman who owned a blacksmith shop in Mahanoy City about the time, and sold out and went away, and after his work at the tunnel was done, Mr. Reidinger brought this shop of the first buyer and ran it for many years. The Philadelphia and Reading Co. did not buy out The Little Schuylkill Co. Some of the directors were the same in each company, and about three of four year after the road was working the P. & R. Co. leased the road from the original company for a period of thirteen years. At the expiration of that time the Philadelphia and Reading re-leased the railroad from the Little Schuylkill Company for ninety-nine years, which last leased is still running.

The followings Mr. Reidinger’s history of the trouble. He was on the ground at the time, from the beginning to the end, an interested spectator, and an ardent admirer of the Barrys, especially the Superintendent P. J. After the tunnel was completed the Barrys refused to turn it over to the Little Schuylkill Company until they received the money due them from the company, which was sixty thousand dollars. The contractors owed the men three months’ wages. The Superintendent called the men together and told them that if they stand by him he would not give up the tunnel until he had received the full amount due. If the men would stick to him, and help him to hold the tunnel, then the company would have to pay him and he could then pay the men the wages owed to them; but if he gave up the tunnel, he might have to wait a long time for his money, maybe have lawsuits and delays of all kinds, and the men would have to wait maybe for months or years for their wages. The men enthusiastically agreed to a man, to stand by their contractors, and not surrender the tunnel until every dollar of the contract money had been paid. At the west end of the tunnel they built a barricade, consisting of an eight-foot wall with port holes, and four cannon were planted behind these walls. The company had threatened to take the tunnel by force, and the men were determined to fight. The company sent up engines from Girardville, time and again, requesting to be allowed just to run through the tunnel, but the men refused. Fearing the company might try to come through the east end from Tamaqua, the men built a guard house at that end and manned it with two hundred men, with guns and ammunition, victuals and forty barrels of whiskey. As soon as the equipment ran low more was bought, so that the men were sure of plenty of sustenance. Besides their guns, they also had cannon, two buried in the South Mountain and one on the North Mountain. The Railroad Company, thinking to out-manoeuver the contractors, brought a passenger train from Tamaqua up to the east end of the tunnel and asked to be allowed through; for the answer the Superintendent ordered the cannon to be trained on to the engine. It did not take the engineer long to back his cars out of danger. Hearing that the company were contemplating coming from Girardville with a train, P. J. Barry took three hundred men and, between daylight and daylight, tore up the tracks and threw the rails down the embankments all the way from Giradville to the Tunnel.

Then the president of the company went to Governor Andrew G. Curtin and asked him to send troops down to Schuylkill and force these men to surrender the tunnel to the Little Schuylkill Company. Hon. Francis B. Hughes was the counsel for the Barrys. He hastened to Harrisburg and laid the whole matter so forcibly before the Governor that Governor Curtain sent for the president of the railroad and, in the presence of the eminent lawyer, told the president to go to the contractors and pay them the just amount that the railroad company was indebted to them, and then if the Barrys did not surrender the tunnel he, the Governor, would take the case up again. That was the last of the controversy. The company paid the contractors, the contractors paid the men, the roadbed was rebuilt, the tunnel was turned over to the company, and the men quietly dispersed. To show the way the Barrys worked in order to have the tunnel completed on contract time, Mr. Reidinger stated that for weeks at a stretch the men would work three shifts, two days and a night, or two nights and a day, without sleep, then take one shift for rest and begin again. That he himself, in order to keep up with his work, he stood at his forge four shifts at a time, and more than once he worked seven shifts, or four and one-half days, without rest.

Transcribed by LaRue Flammer for the Mahanoy Area Historical Society

Enlargement of the East Mahanoy Tunnel

East Mahanoy Railroad

By P.A. Taylor, Member of the Club

Read December 20th, 1884

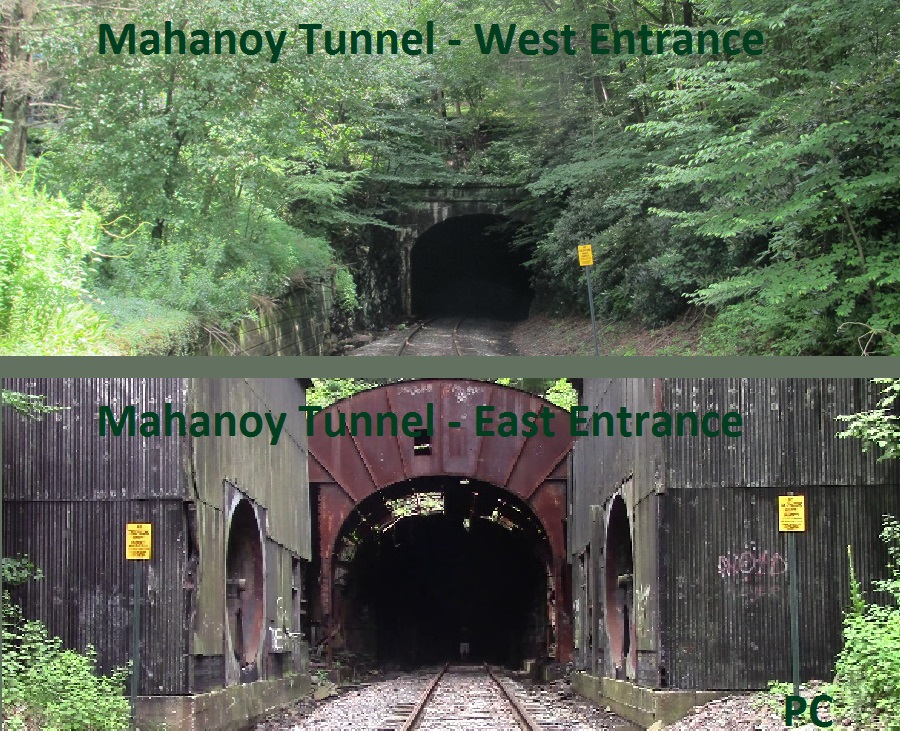

The East Mahanoy Railroad is a branch of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, of which it is a very important feeder. It commences at East Mahanoy Junction and terminates at Waste House Run, in the Mahanoy Valley, a distance of about eight miles. It runs through the Broad Mountain by a tunnel 3,411 feet long, the construction of which was completed in 1862.

In the spring of 1876 it was decided by the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad to enlarge it, on account of it being too low to permit the passage of engines having the standard height of smoke stack adopted by the Company. The stacks of all engines running through the tunnel had to be cut down, and as the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad Company were desirous of having all their engines of a uniform height, the enlargement was made.

To do the work it was first thought that a sufficient amount of roof could be taken off, but on account of slips and rocks falling caused by the cutting through several of the coal measures, when driving the tunnel, this was particularly dangerous, and necessitated timbering in some places; the risks also of detaining trains, by having the necessary false works in the tunnel to reach the roof, was great, and, the coal trade being particularly brisk at that time, the idea was abandoned, and it was then decided to take out the bottom, a portion of one side, and part of the bench that had been left in originally by the East Mahanoy Railroad Company.

The work was started on May 9th, 1876 and finished September 9th of the same year, costing about $41,000. The length taken out was 3,411 feet; average depth, two feet; and width twelve feet- all of which was through conglomerate rock, known only in the anthracite region. In addition to taking out the bottom, various points f the roof had to be taken down, as well as the side of the tunnel, as noted above.

A force of about 225 men was employed in the work, one- half working during the day, drilling holes for the blasts, and getting everything ready for the explosion of the shots, which generally took place about ten o’clock at night, after the fast Centennial Express had passed through. The night force was employed in blasting. Number two dynamite was used, and 100 shots put off at one time with electricity. The debris was then cleared away and the track blocked up to allow the trains to pass through. From ten o’clock until two o’clock, during the night, was the only time that trains entirely ceased to run through the tunnel.

The work was first put under contract to the late Philip Steinbach, of Schuylkill County, who lost on the work. The Philadelphia and Reading Railroad Company paid him his losses, and directed the work to be done by Mr. H.K. Ncholas, Resident Engineer at that time, now Chief Road-Master. The writer was an assistant of Mr. Nicholas, and had charge of the details under his direct supervision. We labored under great disadvantage for want of proper ventilation. The shafts which had been sunk during the construction of the tunnel had been filled up for some years, and the smoke caused by the numerous trains passing through, as well as that produced by the blasts, had to seek an outlet at the east and west ends of the tunnel. This was specially the case during the low stage of the barometer, and some days it was barely possible to do any work whatever, owing to the gases produced by the engines passing through. These points are simply mentioned to show that, with all these delays, we consider the work was done in a very short time.

During the whole progress of the work but one train was delayed, and that only five minutes, and the only accident that occurred was the killing of one laborer, caused by his falling under the small engine which was used for hauling away the small trucks loaded with debris from the tunnel.

In the grades of the original roadbed of the tunnel there was a slight adverse grade from the west end to a point about midway, causing water percolating through the seams of the coal measures to drain partly into the Susquehanna and partly into the Delaware. Now there is a continuous grade with the trade, obviating a heavy pull of the loaded coal trains after entering the tunnel.